Mary Anning (1799–1847) was a famous English fossil hunter and collector. Despite her poor background and limited education, she was the first to discover and identify many important pre-historic fossils. She lived at a time when women were rarely taken seriously in science. During her lifetime she received little recognition for her work, despite helping to change our understanding of ancient creatures and evolution. Find out more about this dedicated and determined woman, and use our printable resources to celebrate her life.

Fun Facts

- When Mary was just 15 months old, she survived a lightning strike. A neighbour was looking after her, while standing under an elm tree with two other women. Lightning struck the tree and all three women were killed, but Mary miraculously survived. She had been a sickly child, but after the strike seemed to have robust health. Many people also believed Mary’s intelligence, determination and lively personality were triggered by this incident.

- It is said that Mary Anning’s life inspired the tongue twister ‘she sells sea shells on the seashore.’

- Mary only made one trip away from home in her lifetime, to visit London.

Mary Anning Quotes

“It is large and heavy but… it is the first and only one discovered in Europe.”

“The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.”

A Short Biography of Mary Anning

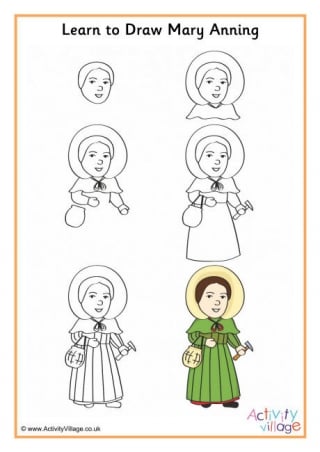

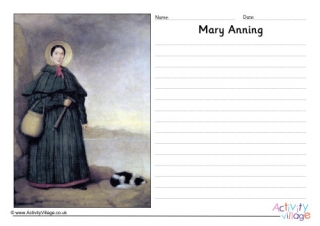

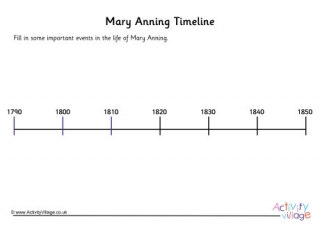

Mary Anning was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, Dorset, England. She was the eldest of ten children born to Molly (Mary) and Richard Anning, but only Mary and her brother Joseph survived into adulthood.

Mary’s father was a carpenter by trade, but also a keen amateur fossil hunter. To supplement his income, he would clean and polish fossil findings and sell them to tourists on the beach. Mary learnt much about fossil hunting from her father. The cliffs near their seaside home had lain beneath the sea 200 million years ago. Now they were rich in the fossilised remains of prehistoric sea creatures.

Mary didn’t go to school because her family needed her to earn money, but she learnt to read and write at Sunday School. She began to teach herself about rocks and anatomy (body parts) and learnt to draw very detailed and accurate drawings of her fossil findings.

When Mary was 11, her father died from a disease called tuberculosis and injuries he had sustained during a cliff fall. The family were grief-stricken and left even poorer than before. Mary was determined to support her family. She went fossil hunting most days with her dog, Tray. She particularly liked hunting after a storm, when the waves, wind and rain caused the rocks to crumble.

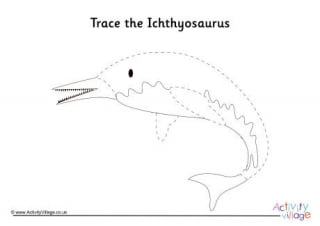

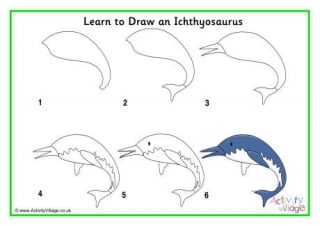

In 1811, just a year after their father’s death, Mary and her brother were out fossil hunting when Joseph saw a skull within the rocks. A few months later, Mary returned and slowly uncovered the rest of the skeleton. It turned out to be a nearly complete 17-foot skeleton of a marine reptile from the time of the dinosaurs. Mary sold the skeleton to a local collector for £23, and it eventually went to London’s Natural History Museum, where it was named Ichthyosaurus (‘fish lizard’) in 1817.

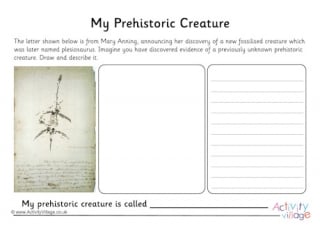

People had found fossils before, but no-one understood what they were, and no-one knew about dinosaurs. Mary also discovered a flying reptile (pterosaur) in 1828. But perhaps her most important find was in 1823, when she unearthed the complete skeleton of a nine-foot swimming reptile, later named plesiosaur.

Mary shared her knowledge with important scientists of the time, who came to visit her and the fossils she had found. But the scientific world was not so kind. Many articles described her work but didn’t reference Mary, and many of her findings joined important fossil collections with no credit given to her.

In 1826, Mary opened a shop in Lyme Regis. She sold most of her fossils to support herself. But in 1838, was granted an annual income to continue her work from the British Association for the Advancement of Science and London’s Geological Society. This was despite the fact that, as a woman, she couldn’t become a member.

Mary died from breast cancer in 1847, at the age of 47. She had never married and her only surviving family were her brother Joseph and his wife Amelia. Mary was buried at Lyme Regis Parish Church, where later the Geological Society paid for a large stained-glass window to be installed in her memory.

Our Mary Anning Resources